A Forgotten Calamity

A Forgotten Calamity

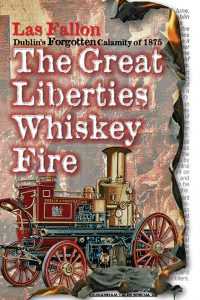

DFB historian Las Fallon talks to Adam Hyland about his new book on the Great Liberties Whiskey Fire of 1875.

Among the strange and eye-opening stories that lie within Dublin Fire Brigade lore, the fire that threatened to destroy a large part of the south inner-city in 1875 when a whiskey warehouse suddenly began throwing flaming liquid into the streets is probably one of the strangest. Stranger still is the fact that many elements of the story have remained unknown, but in his latest book, DFB historian and former firefighter Las Fallon has pieced together the events of that night. The Great Liberties Whiskey Fire details what happened, and the repercussions from a bizarre incident when burning whiskey flowed through the Liberties, much to the delight, then dismay, of the citizens of Dublin.

“The story of the whiskey fire interested me particularly because it happened in my area,” Las tells me. “I was a firefighter in Dolphin’s Barn for 30 years, so the Liberties area was just down the road. I had fought fires on those streets, and knew the area.

“I’d heard of the whiskey fire before, but it was one of those stories that had grown legs over the years, so I had sort of written it off as an exaggeration. But the first mention of it I read was in Tom Geraghty’s work on the history of the Dublin Fire Brigade, and all of a sudden, I realised, oh, this did happen, and it was on the scale that people had told me about.”

With his interest piqued, Las started researching and found old British newspaper archives containing illustrations to accompany the reports.

“Once you see the illustrations depicting the scale and madness of the incident, I got very interested,” he tells me. “These images were not favourable to Irish people, and even though there was probably some exaggeration, not every one of these newspapers could have been exaggerating the incident, so I began to see how big the story was. It was essentially the largest fire in Dublin in the 19th century in terms of the area affected, in financial terms, and in terms of loss of life. I started looking into as many records as I could, anything I could get my hands on, and slowly started to gather the story together.”

THE STORY

The story itself is a remarkable one. On 18 June, 1875, a huge bonded whiskey warehouse in the Liberties area containing at least half a million litres of whiskey owned by Dublin’s major distilleries, suddenly erupted in flames, sending burning whiskey flowing into the streets. The fire quickly spread along the narrow roads and alleyways, igniting buildings and sending the city into a panic. Locals, however, ignoring the obvious danger, saw their chance to enjoy a free drink, and reportedly began scooping the whiskey up into whatever receptacle they could find, or simply drank it straight from their cupped hands. Word of this sudden bonanza spread as quickly as the fire, and soon the streets were packed with people, increasing the danger and adding to a scene of mayhem.

Responding to the fire were just 15 men from the then newly-established Dublin Fire Brigade, led by their Fire Captain, Robert Ingram. Aided by 150 policemen and 200 soldiers, their actions and quick-thinking helped quell the fire and save the city, but not before 13 people had consumed lethal amounts of spirits.

The story has never been fully told, until now. Las was approached by Micheál Ó Doibhilín of Kilmainham Tales, who had seen Las talk on the subject, and suggested he put pen to paper and write a book about the fire.

RESEARCH

The timing was also perfect for a book on the whiskey fire, with the rejuvenation of the whiskey industry in the very same area of Dublin city taking hold, but while more material was coming to light, there were still many problems in finding all of the details regarding the fire and its aftermath.

“One of the big problems I had was that I knew 13 people had died, but I couldn’t find any trace of them,” Las says. “I went to the register of deaths, but unless you know the name of the person who died, you won’t find them.

“I went into the national archives, got the coroner’s records for Dublin, but nothing was coming up. I did find a report of a woman who had died of alcohol poisoning a few days after the fire, so that was a starting point. Eventually I turned up five names, all of whom died in the same way in the immediate aftermath of the fire.”

The information that could be gathered showed that Dublin at the time had a thriving whiskey industry. A change in the licensing act in 1823 meant that distillers only had to

pay tax on their whiskey when it became available for sale, rather than when it was first barrelled, and this opened up the market to commercial bonders who would store the barrels for the distilleries.

Lawrence Malone quickly became the biggest name in the bonded warehouse business, establishing a huge storage warehouse in the Liberties. “There were others, but Malone was the biggest,” Las tells me, “and while he created an industry in Dublin, he also created a ticking timebomb. There was now a huge amount of flammable liquid in one huge building, sitting behind narrow city streets, without any provision for fire safety.”

The cause of the fire remains unknown, but what is strange is that the first reports describe it as a major fire bursting through the roof of the warehouse, some 30-foot high. “It must have been burning for some time before it got to that level, but nobody reported smelling smoke, nobody saw anything, until it was fully developed,” Las says.

MAYHEM

When the fire was reported, the Dublin Fire Brigade (which consisted of just 23 men, 15 of whom were available including Fire Captain Robert Ingram) arrived within ten minutes, and when the Police got to the scene, “they obviously got a sense of not just what was happening, but what might happen, because they sent for massive reinforcements of 150 men,” Las says. “Two premises were on fire, flames shooting into the air through the roof, flammable liquid was flowing out under doors and through windows, blue flames flowing down the streets. It’s the worst of two possible calamities – a flood finding its way under doorways and into houses, into every crack and crevice and down every street and alley, and it’s also burning as it goes. They couldn’t put water on it because it is already liquid, so it was like petrol. There’s also a very steep drop on those streets.”

Soldiers – some 200 – were also sent for. “Soldiers were important because they could help with salvage, but also man the pumps so the firefighters could use the hoses, and control the crowds, which was becoming ever-more important,” Las tells me. “Some soldiers arrived armed and threatened a bayonet charge on a group of citizens who attacked them as they tried to guard 60 barrels of whiskey that had been salvaged.” The utter chaos of the scene is hard to imagine, even with the vivid illustrations of the day.

“There were 13 deaths, but not one of them was caused by fire itself,” Las says. “They were all to do with the madness that took hold. Some of the stories were very sad, but some of them were also bizarre. My favourite is the house where there was a wake going on. The people there put themselves at risk to save the corpse, but they only save him enough to make sure he doesn’t burn, before they all run back to get themselves some free whiskey. I like that because it is just so human.

“The madness started early, as soon as it became clear that this was whiskey flowing down the street. The thing was that it was a mixture of whiskey, immature spirits, probably some brandy and wine too. The sight would have been unusual. People wouldn’t have seen this type of flaming blue liquid before, like the flames on a lit Christmas pudding, but on a massive scale.

“Buildings started to burn with proper fires as well as this burning liquid fire, and a tannery went on fire. At the time, many people kept pigs to supplement their family income, while there were also a large number of stables in the area, so when the fire broke out, there were animals everywhere, pigs, dogs, horses running around.”

SAVING THE CITY

Captain Ingram came up with an ingenious idea, Las tells me. “He realised that he needed something to slow the whiskey fire down, and soak it up, something organic. That’s when he decided to use the holy trinity of ashes, tan and manure, because that’s what was available. It was a poor area, so there were a lot of tanneries around. It was brilliant thinking. A hundred years later they would have fought the fire with foam, which is organic too, so using what was available, he was a hundred years ahead of his time.”

Ingram’s actions were successful, managing to first block and then extinguish the many fires that had been caused by the flaming blue liquid. “Had they not contained that fire, it would potentially have flown to Christchurch and could have destroyed a huge area. In theory Christchurch itself could have been in danger,” Las says.

A FORGOTTEN STORY

Though the DFB had saved the city, the story was very quickly forgotten about, even to this day, and as Las explains, there were many reasons for this.

“In the immediate aftermath of the fire, Dublin became a laughing stock,” he says. “There happened to be a huge number of British and American journalists in town to cover a rifle match in Sandymount, and they were witnesses to this bizarre event. The press wanted local colour, and the scenes they saw were gold to them. You couldn’t make it up. There was no point in writing about a big fire in Dublin for American or British readers, there were big fires everywhere, but the story of Irish people running around, the streets in flames, scooping up and drinking whiskey off the road had been played up by the British and American press.”

Because of this, the Irish press quickly began to play the incident down. “There was a sense of embarrassment,” Las tells me. “We made eejits of ourselves, had fulfilled every stereotype. Within days the papers were talking about the great law-abiding citizens. On the night itself you couldn’t move for the amount of people trying to get to the whiskey, but suddenly the story was changed and they were all law-abiding citizens who came to offer assistance.

“The whiskey industry, which was huge, didn’t want the story to be of people drinking their product and dying. So, they used their influence to play it down. Social norms at the time also meant that poor people were considered as lesser, so 13 poor people dying was quickly forgotten. If the fire had been at Merrion Square it would have been a different story.”

Nevertheless, some important legacies did arise out of the incident. “Fire safety and the fire brigade having a role in it were still 100 years away,” Las says, “but this made the distillers aware of the fragility of their product. They started to set up fire brigades of their own within the distilleries.

“The major legacy is that this fire happened only 13 years after the establishment of the Dublin Fire Brigade, and there were still a lot of people in the city who didn’t understand why Dublin needed a full-time fire brigade. It was seen as an unnecessary financial burden. But all of a sudden, they realised that but for the fire brigade, there would have been a major incident that could have destroyed a significant part of the city, and the businesses within it. So, in a way it was the incident that justified the fire brigade. It was the fire that showed their importance. They saved the city.”

CAPTAIN INGRAM

The loss of 13 lives is obviously tragic, but to some degree the fate of Captain Ingram is also tinged with sadness. Though he was the father of the Dublin Fire Brigade, his legacy is almost forgotten. “Ingram died in 1882, and he just seemed to slip by in the history of Dublin,” Las tells me. “There is no statue, nothing to commemorate him, there is only one, blurred photo of him – which is strange given that he lived in a time when photography was becoming established – and his grave is an unmarked patch of dirt in Mount Jerome cemetery.

“He was promoting a fire service that the business people of Dublin didn’t want. It was for the benefit of everybody, but not everybody was paying for it, is how they saw it, and so he fought an uphill battle to have the organisation recognised, and his own input acknowledged. I hope this book can bring him and his contribution to the fore for historians and the people of Dublin alike.”

The Great Liberties Whiskey Fire by Las Fallon is available online from www.kilmainhamtales.ie and from Teeling’s Distillery and the Irish Whiskey Museum. Kilmainham Tales is an innovative publisher of academically rigorous but affordable and easily read books covering the period during which Kilmainham Gaol was in operation (1796 – 1924). Listen to Las talk about the fire on the Three Castles Burning podcast here: https://tinyurl.com/s9gtvb2