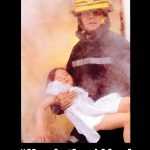

Above: Marion and Rory.

Conor Forrest sat down with retired firefighter Rory Mooney, who spoke about his career with the brigade and his voluntary work with orphaned children affected by the Chernobyl disaster.

It’s more than 36 years now since the tragic Stardust fire that saw 48 people lose their lives and a further 214 injured when flames tore through the popular nightclub on Dublin’s northside. The harrowing events of that night have echoed through the proceeding decades, with the findings of the tribunal of inquiry – which concluded arson as the likely cause – disputed ever since. One of the emergency responders on duty that night was Dublin Fire Brigade firefighter Rory Mooney, relatively new to the job having joined in 1978. Despite having been marked for ambulance duty, a colleague on sick leave meant he was tasked with manning the phones that night.

“That was a totally different ballgame,” he explains. “The records of the Stardust are all in my handwriting. I ended up eight hours on the stand giving evidence in the Stardust Tribunal. The only person who spent longer on the stand, I believe, was the Chief Fire Officer T.P. O’Brien. Nothing could prepare you for it. I just answered as best I could. ‘And why did you do that?’ ‘Because that’s the way I was trained’. Simple as that.”

Rory’s 31-year career in the brigade began, as with all recruits back then, with a stint in Tara Street, following 14 weeks of training in Kilbarrack – one of the last classes to do so. He recalls being handed the job of being ‘on the bunk’ at headquarters on his first night, manning the phones from midnight to 6am, and taking the 6am to 9am early relief shift the following morning.

“It’s all computerised these days, but it was pen and paper in my day,” he explains. “But it was good, it was an education in itself. During our training we had to go into Tara Street at least one or two nights and visit the control room and see how it worked, give yourself an insight into what was going on in the place.” After five years in Tara Street, where he joined other junior men in manning the northside stations whenever there were shortages, Rory was posted to Buckingham Street station on D watch for three years, before moving to Phibsborough where he would spend the rest of his career, eventually retiring in 2009. Back in those days, he says, the ambulance was as busy as it is today, even in 1978. “If you were in work and you knew, for example, that you were on the ambulance on a weekend night, you’d make sure you were well fed and watered before you go into work,” he says. “We were normally very well. received wherever we went. Especially on the ambulance – anywhere we went people knew we were there to help them. [But] as Nobby Clarke used to say, ‘If your budgie doesn’t sing, call the fire brigade’. And sometimes it seemed like that.”

Rory’s collection of memorabilia.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

For Rory, what brought him into work every day was the opportunity to make a difference to the lives of Dublin’s citizens. “We went out when people were at their lowest, and I mean utter lowest,” he explains. “Their house could be burning down around them or their father may have died, and we would arrive. We tried to make things better. It’s not always possible – sometimes you have to do a bit of damage in a house to put out the fire, but we tried to leave the people and structure in a better shape than [when] we found it. That’s what we’re there for really.”

Rory’s desire to help people in wretched circumstances would take him beyond Ireland’s borders. In 1986, while he was based in Phibsborough, the Chernobyl disaster shook the world. On April 26th the No. 4 reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine was destroyed, releasing radioactive material into the atmosphere, with the fallout spreading across western USSR and Europe. Thirty-one deaths have been directly attributed to the disaster, alongside deformities and defects in children born in Ukraine and Belarus in the years after the explosion.

“Radiation knows no territorial boundaries, it doesn’t apply for an entry or an exit visa, it travels wherever the winds take it,” said Adi Roche, who founded Chernobyl Children International. “At 1.23 am on 26th April 1986 a silent war was declared against the innocent peoples of Belarus, Western Russia and Northern Ukraine. A war in which they could not see the enemy, a war in which they could send no standing army, a war in which there was no weapon, no antidote, no safe haven, no emergency exit. Why? Because the enemy was invisible, the enemy was radiation.” Many of those children wound up in orphanages, grim facilities that provided a roof over their heads and regular meals, but precious little else in the way of a normal life. Stirred by their predicament, Rory joined convoys travelling 1,500 miles from Ireland to Belarus by ground, carrying much-needed medical and humanitarian supplies for the recovery efforts.

“A lot of firefighters died, a lot of children died, and being a father and a firefighter, it tugged at the [heart] strings. So when I had a chance at getting involved I did,” says Rory. His first trip over was in 1996 and by chance he met his future wife Marion the following year, travelling as part of the same convoy. Everything fell into place and their first wedding was at a Russian Orthodox Church on May 4th 2003, but they discovered the marriage wasn’t legal back home. After a four-year wait they were married again in Wales on May 5th 2007. As Marion describes it, “We tried to get as close as we could. So we’re married ten and 14 years!”

Rory and Marion made the trek to Belarus twice a year for 12 years in total, working with the manual team building playgrounds, putting roofs on portacabins, painting wards, renovating shower facilities and whatever else needed to be done. “You carried the kids out to the open air, you put them on swings and roundabouts and you’d amuse [them] for a couple hours during the day. It was very depressing when you’d leave the orphanage because you’d feel very guilty leaving the kids behind,” he recalls. Alongside supplies of medicine, furniture, clothes, shoes and much more, the teams also brought gifts for the children in those institutions – simple items like balloons or rugby jerseys that nonetheless made their day. “To see their faces – you’d give them a jersey and they knew it was theirs to keep, because they were used to being handed gear and it being taken from them,” Rory adds.

Rory also made contact with the fire service in Belarus, an under-resourced organisation that did the best job with what it had. On his first trip he brought over a retired hydraulic cutting tool, which was received with great enthusiasm. As luck would have it, that was placed on a tender with the call sign 32 – Rory spent a lot of time on 3-2 based in Phibsborough. That kickstarted a relationship that would last for years, with the Dubliners bringing a gift of equipment each time, including incubators, infusion pumps and even a laparoscopic instrument for keyhole surgeries. Introductions were made with the Chief Fire Officer, they were brought on tours of the fire brigade training college and their museum, and they were made a gift of Russian Fire Brigade china, now on display in the Dublin Fire Brigade museum at the training centre in Marino. Rory’s colleagues in DFB were instrumental in getting them across the continent every year. Alongside an annual bucket collection on O’Connell Street, the Workshop fitted a fire brigade van with a bed, cooker, fridge and portaloo purchased by Rory and Marion, and insured the pair to drive it. “The Chief Fire Officer at the time was great,” he adds. “He couldn’t do enough charity-wise. ‘What do you need Rory?’ he’d say.”

THE QUIET LIFE

THE QUIET LIFE

The last few years have by no means been easy for Rory and Marion. Illness forced him out of the job he loved in 2009, having been diagnosed with lung cancer for the first time a year earlier – less than a year after he and Marion were married in Wales. Alongside a back operation and pneumonia he suffered a stroke in 2016, leaving him with short-term memory issues. To make matters worse, doctors found cancer in his other lung while undergoing tests. A tough situation that’s unimaginable unless you’ve gone through it, it’s clear that the same black humour that many firefighters use as a coping mechanism helped him through some difficult times – he recalls asking a surgeon during his first bout of cancer to save ‘a bit of meat for the cat’.

“It’s not a death sentence, it’s just a word. And if you can hang onto that it makes it a bit easier to deal with,” he says. “And it’s not easy to deal with because you don’t know if you’re going to survive, you don’t know if you do survive what way you’re going to be after it. But we got through it. We got through it together.”

It’s also clear that his career as a firefighter means a great deal to him. A shelf above his stairs (Marion’s handiwork) is home to a collection of memorabilia including helmets, patches and medals, a selection of statues received on his retirement takes pride of place along the fireplace, while two detailed and colourful statues of firefighters, souvenirs from Belarus, stand on duty in the back garden. There’s also a more unusual item – half of a good-sized rock that was thrown through the window of his ambulance as he and Leslie Crow travelled along the Navan Road one day, narrowly missing his ear.

Rory keeps in touch with old colleagues too – he joined the Retired Members Association last year, pops into Phibsborough fire station every few months for a visit, helps Paul Hand in the museum every Thursday, and is one of several veterans of No. 3 known as the ROMEOS – Retired Old Men Eating Out – who meet up every few months for dinner and a catch-up. These are friendships cemented over decades, between people who often placed their lives in one another’s hands.

“Nobby Clarke, the Crow [Leslie Crow] – Leslie was one of the best firefighters I ever worked with. I trained as well with Paul Hand, the curator of the museum in the OBI. He is one of the hardest working firefighters I’ve ever met in my life, he really is,” Rory tells me. “You’re in situations where your life could literally be hanging on your friendship with somebody else. It’s very much a second family. It was never just a job. You go into it [at the beginning] and it’s just a job, but once you’re there a while it’s a heck of a lot more – it’s a way of life.”